Visiting the Verdun Battlefield

We’re a couple of hour’s drive and a million miles away from the vineyards of Champagne. We’re using a riverside Camping-Car Parks aire at Charny-sur-Meuse as a base to explore the Verdun WW1 battlefield (€14 a night including services and electricity). The village is south of the front line from WW1, but nevertheless was wiped off the map and rebuilt anew in 1919 (more about the village here).

After a silent, starry night beside the vines at Martigny we headed here first via the toll-free D and N roads, stopping at a huge hypermarket for supplies. When we came to leave, I turned the key in the ignition and nothing happened. At least nothing we wanted to happen. A bunch of weird clicking and whirring noises erupted from the cupboard holding the van’s Elektroblock EBL (the gubbins that controls the electrical system). No lights appeared on the dash, the starter battery was totally dead.

Cutting a short story shorter, the ground lead had worked loose from the battery terminal. I tightened it, turned the van’s 12V back on all was good. Phew! The van started and everything worked in here. I admit to being very relieved! Yep, we’ve European breakdown cover, but having had to use it a few times abroad, we’d prefer not to. It’s a time-consuming hassle. Thanks again to the massively helpful denizens of the Hymer Owners Group on Facebook for pointing the way.

With elevated stress levels we cheerfully shelled out a few Euros on the nigh-on-empty toll motorway. Pulling away from the last toll booth and onto the minor roads, helmets sat atop the milestone markers told us we were on the famous Voie Sacrée (“Sacred Way”), now named the RD1916. I’d read up a bit on the Verdun battle before we arrived, and this minor road was pivotal to the entire thing. When we came across a monument besides the road, we pulled in to read the information and look around.

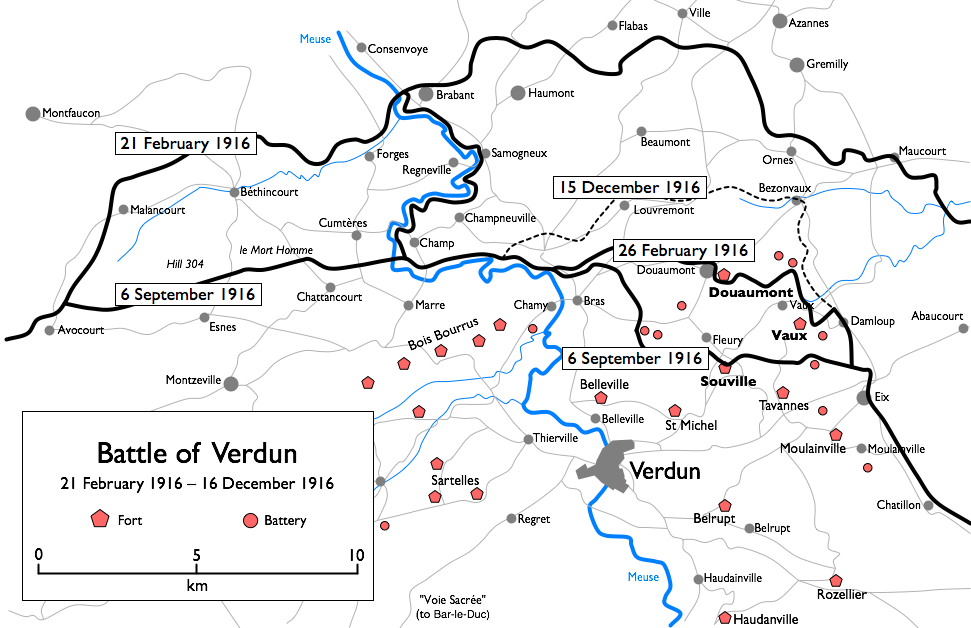

Summing up one of the bloodiest events in human history into a single paragraph (this article has the detail): the Battle of Verdun was a 300-day long tooth-and-nail fight between the French and German armies in 1916. The Germans launched a huge attack on the front line here, hoping to break through and quickly put an end to the war. It didn’t work. The French held them back at enormous loss of life. The losses for both sides totaled roughly (no-one knows exactly) 300,000 killed or missing, and another 400,000 wounded.

The Sacred Way was vital as it was the only road from the south running up to Verdun, although there was also a narrow gauge railway line and a canal. It wasn’t even paved at the time. To get the men, ammunition and supplies to and from the front, 600 trucks per day in a constant stream used the road. Quarries were re-opened and stone thrown under the wheels, with a truck passing every 15 seconds. Any vehcile which broke down was shoved into the ditch. This huge scale, sustained effort enabled the French army to keep going.

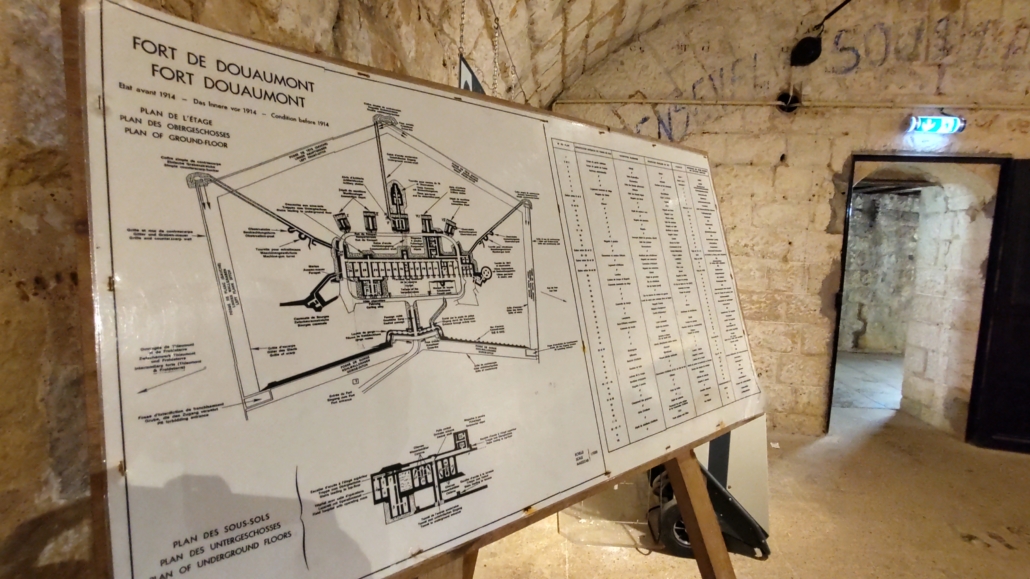

This swift reaction by the French military leadership is in contrast with a serious error in judgement prior to the battle. The French had initiated and lost an earlier war with Germany, and in prescient fear of a further conflict, had built a double ring of 28 forts around Verdun. In earlier fighting in WW1 similar forts had been easily destroyed, and the French decided these too would be of little value, and had removed many of the large guns and men. In retrospect those other forts were made without reinforced concrete, while those here were full of reinforcement metal and turned out to be very tough indeed.

This thinking led to the underground fortress at Douaumont, a short drive from us here, to be hardly manned. A few German infantry managed to take it without a shot being fired, after sneaking in through a window and opened a door. The entire German nation celebrated and school children were given a day off. One estimate put the number of French lives lost as a result of this calamity at 100,000 as it proved very hard to retake.

The Germans in turn suffered a catastrophe in the dank innards of the fort (you can tour inside for €5). Myths and legends created or perpetuated for propaganda purposes, abound. Exactly what happened at Douaumont is the subject of much conjecture. Whether it was a French shell impact, a cooking oil accident or someone trying to heat coffee by burning flamethrower fuel, a fire broke out close to stored munitions.

Further (dubious) speculation has it that German soldiers covered in soot were mistaken for much-feared black-skinned soldiers from French Africa, and were attacked by their own side with grenades. Whatever the cause, the end result was a giant explosion followed by asphyxiation. The fort was packed with thousands of men at the time and around 800 died in this single catastrophe. Unable to bury the dead outside the fortress due to French attacks, the bodies were stacked in corridors and walled up. They remain there today.

Another myth surrounds the Trench of Bayonets. Legend has it French soldiers under artillery fire remained at their posts holding their rifles when the trench was collapsed by explosions and they were buried alive. The reality is, it seems, only a little less horrifying.

A surprise attack on the trench network annihilated the 137th Regiment of French infantry almost to the last man. As was common at the time, the Germans filled in the trench, marking the graves of each man with an upended rifle sticking out of the ground. The bayonets were added later, apparently as part of the propaganda war. Eventually most of the bodies were exhumed and identified, a handful of unknown men were reburied and the trench was covered with a concrete monument.

Douaumont Fort and the Trench are located with a few miles of each other, surrounded by dense woodland. We didn’t notice at first, but the land beneath the trees is one huge mass of craters. And I mean huge, they’re everywhere, for miles. 60 million shells were fired here. That’s six for every square metre. Practically everything was obliterated. Farmland and villages disappeared.

A large number (many millions) didn’t explode, including poison gas shells. Most are still there, along with the remains of an estimated 80,000 men who were never found. These huge areas of unusable land were declared ‘Red Zones’ by the French Government after the war. Nothing was rebuilt there and no farming could take place. It’s an eerie sensation knowing your walking among all of this.

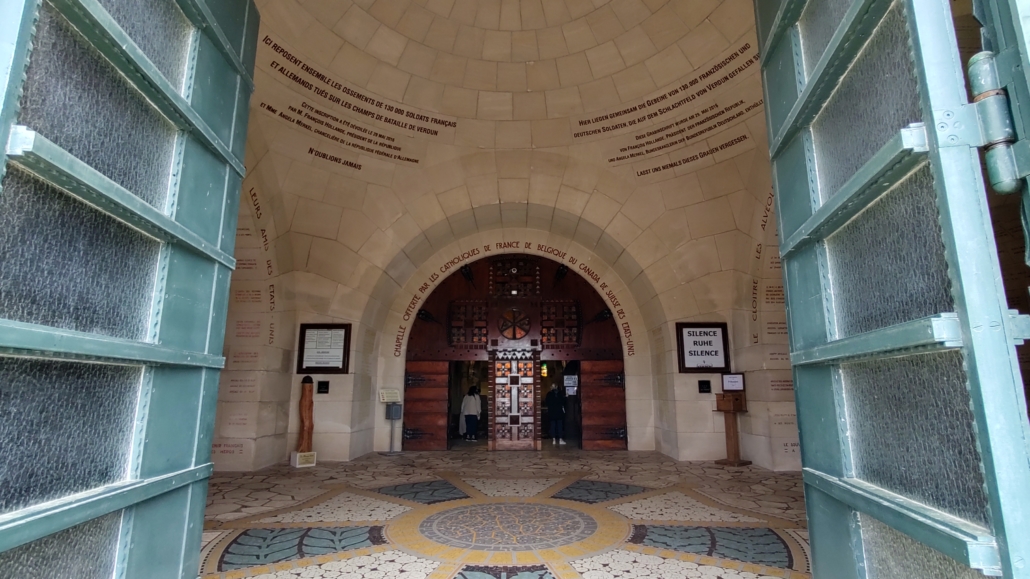

Of the dead who were found, at least 130,000 couldn’t be identified (which I guess this means they were blown to pieces, burned beyond recognition, too decayed etc). Following the end of the war their bones were gathered and placed in a big shed. Following a worldwide fundraising effort, the more fitting and permanent Douaumont Ossuary was built in white stone.

Like everything here, it’s huge. From small side windows you can look upon stacked skulls, thigh bones, ribs, pelvises and backbones. They’re jumbled together, French and German, one man and the next. It’s a pitiful sight. To my mind any politician given the power to send men to war should be made to come here and see this, the end results of their decision.

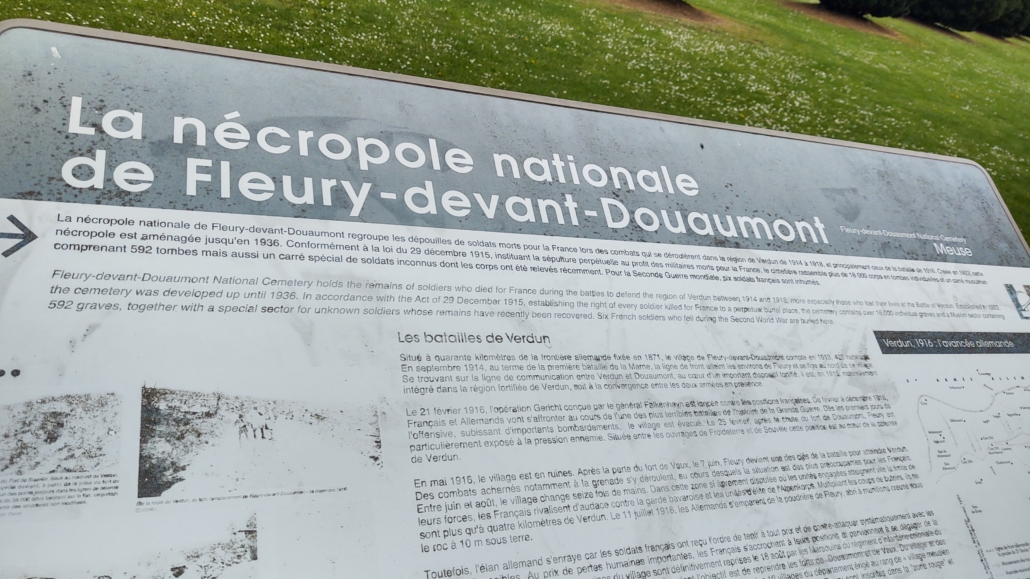

Beside the Ossuary stands the National Cemetery of Fleury-devant-Douaumont with its regiments of white crosses and muslim gravestones (with graves perpendicular to Mecca). The land had to be levelled and cleared of hazardous munitions before it could be used. Some crosses hold up to ten bodies, presumably because they all died in the same area and were too mutilated to be separated.

The graves placed in neat lines, an incredibly moving sight, flowing down the hillside. There are separate monuments to the Jewish and Islamic dead who fought for France in the battle. It contains the graves of 16,142 men, many of whom are unknown. Despite its vastness, it would need to be ten times larger to hold all the French dead from the battle. Some of the crosses have blank name plates, waiting for new remains to be identified and exhumed from the battlefield, over 100 years later.

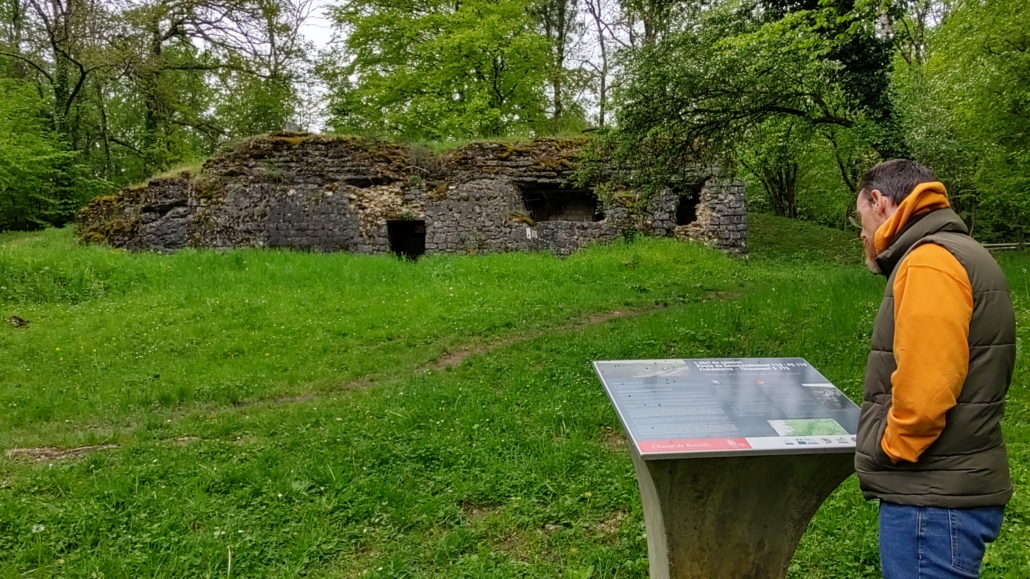

Having been built central to the battlefield, the cemetery is surrounded by the remains of war. It’s here, on the fringes, we got more of a feel for the horror of the place. While looking at the Jewish memorial we noticed signs and paths leading into the forest. These mark out and describe the location of trenches and fortified positions. Chunks of concrete and rebar sprout from the ground, left in place after being blown apart with constant shelling.

We walked a mile or two through the forest, stopping to read the information boards and look around the remains. Unlike the boards at the main memorials, these had testimonials from survivors, over and above the dry facts of the events. Those 300 days were utterly brutal. Men tried to kill each other with anything to hand. Bombs, bullets, bayonets, trench digging tools, poison, bare hands, flame throwers, anything. Men were driven mad from the constant shelling. In Douaumont Fort the audio guide explained how those inside could hear giant shells being fired from miles away, hearing them scream through the air for minutes before slamming into the ground above. Waiting to be blown apart or buried alive.

My childhood memories of war are of the opportunity to demonstrate bravery. To prove you were a man. Films of war depicted men being shot cleanly and falling silently in glorious death for their homeland. War graves and memorials still have this feel to me. They seem designed to say that men died for something important. No mention is made of the horror they endured, or the pointlessness of it all. Both sides usually claim they were fighting for freedom.

Thankfully modern depictions seem to be getting closer to the disgusting, horrific, glory-less reality of it. While unpleasant to watch, we need that, I think, to keep us in check. To remind young (and old) nationalistic men of the inevitable end result.

Jay

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!