The Dragon’s Cave and the Chemin des Dames

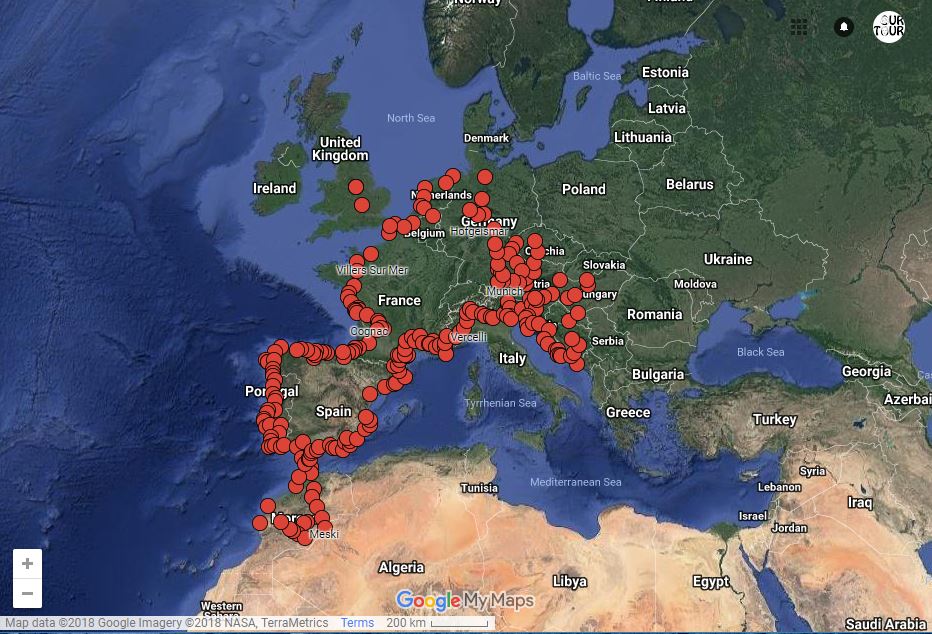

The sun shone yesterday on our campsite below Laon. At home we’ve a small yard bounded by a high wall, not the most relaxing spot to enjoy what little sun we’ve all had these past few months. So we really appreciated the light and warmth on our grassy pitch set beside a wood echoing with birdsong, it was heaven! We cooked and ate outside, took turns to run up and around the ramparts and made the most of the hot showers and pot washing facilities!

Anyone travelling through this area of France will struggle to miss the seemingly endless military cemeteries and monuments signposted from, or literally alongside, the roads. The French alone lost over 1 million men during the conflict, with another 4 million wounded. 880,000 British died, 6% of the adult male population at the time. German deaths totalled over 2 million, over 400,000 of which were civilians. Although it feels wrong comparing one horror with another, purely for scale less than 3,000 people died on 9/11. World War 1 was unthinkably bloody and brutal.

Why? What was the war fought over? Pride mostly, from what I can tell. The whole of Europe was a powder keg before it kicked off, with nations each convinced they were superior to their neighbours. Old grievances, tensions over claims to territories abroad and various alliances all came into play when a young Serb assassinated the heir to the Austria-Hungary throne in Bosnia. The Austrians declared war on Serbia. Serbia’s allies Russia came to their aid. Wary of Russia, the Germans mobilised for war. The French followed suit and in came the British to their aid. Something like that anyway.

During our sunny campsite day I’d come across a WW1 site and museum a few miles to the south of us. La Caverne du Dragon (or Drachenhöhle in German) is famous, it seems, sitting on an equally famous WW1 battlefield named the Chemin des Dames. A lovely-sounding place isn’t it, The Lady’s Path, named after two daughters of Louis XV who used it to frequently visit his mistress.

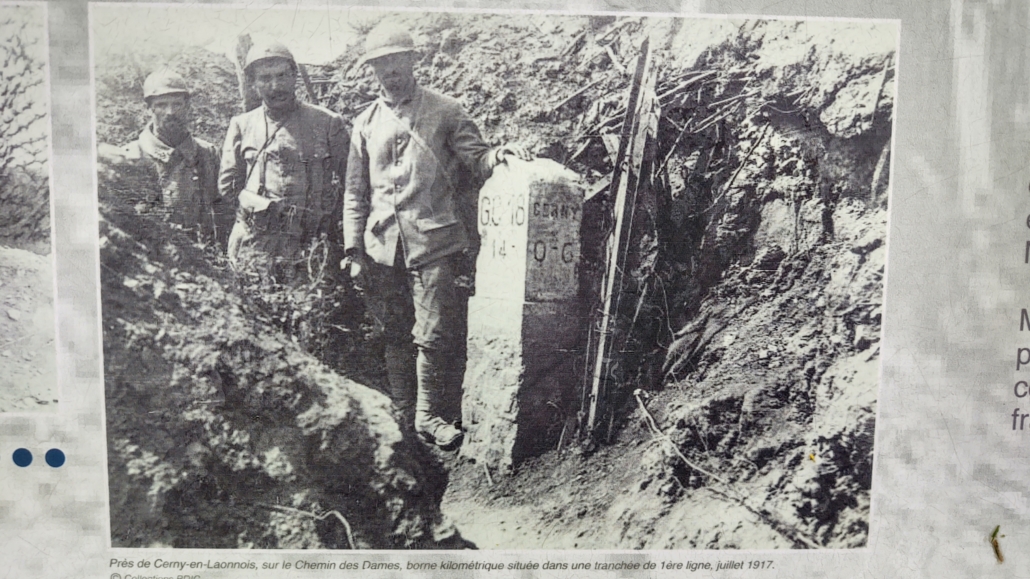

During WW1 the road became notorious as it runs atop a natural ridge in the flowing countryside. Beneath it lies a thick layer of limestone, with over 100 underground caves and quarries dug out over the centuries. Early in the war the German armies stopped the advance of the Allies around here, and used the combination of the height of the road and the caverns beneath to defend it. Unable to advance, the French and British dug trenches and the war became static. The Germans named one of the largest caverns the Drachenhöhle, as the cooking smoke emerging from various entrances reminded them of an old german dragon myth.

Although I’ve heard of names like Verdun, Ypres and the Somme, I’d perhaps never heard of the Chemin des Dames as the French wanted to forget it after the war. If that’s true, I don’t much blame them. Following the monumental struggles at Verdun and the Somme, the French war leadership were convinced the Germans were weakened to the point another large offensive would break through the static lines and drive them back towards Belgium. They were wrong. The brutal battles and senseless mass killing which followed eventually led to mutiny in the French army.

We arrived on the Chemin des Dames part way along, stopping in steady rain to visit a couple of war cemeteries sitting right alongside one another, one French and one German. Although they have their own roads leading to them, a grassy walkway joins them together. Allowed to be peaceful neighbours in death, if not in life. A sign at the entrance to the French cemetery informed us one grave belonged to a mutineer, shot to death by his French commanders. On his cross, like all but a few Russian ones, it reads Mort Pour La France, dead for France.

Heading east along the road, only the signposts for the Chemin des Dames gave away the fact we were somewhere historic. It’s all woods and rolling farmland. The idea that tens of thousands of men murdered and maimed each other over this countryside seems impossible. There’s nothing here. Such is war? A few miles later and something appeared, the concrete and glass of the museum above the La Caverne du Dragon standing incongruous against the landscape.

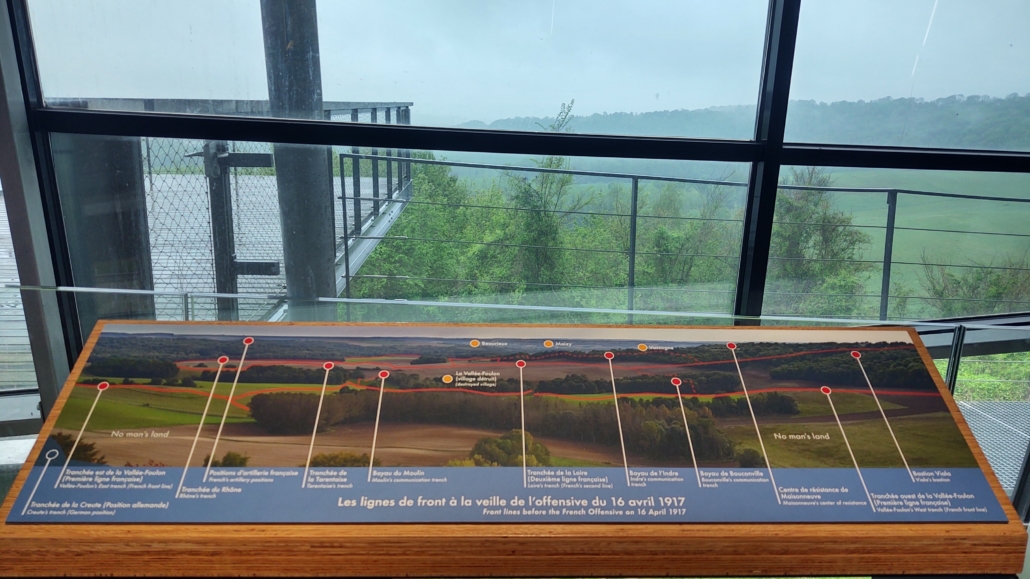

The museum itself is free, and we found it really good with a huge interactive table allowing you to see how the entire bucolic scene around us was a hellish moonscape of blasted trees, trenches and mud 100-odd years ago. To head down into the cavern we paid €10 each (it’s a bit cheaper online but we didn’t know what time we’d arrive, and would have had to wait 2 hours if we’d booked from the car park). You have to go with a guide, and we joined a French group using an English audio guide included in the price.

The tour would have been better in English, it was obvious the guide was telling the others far more than we were hearing and with more poignancy. But beggars can’t be choosers, our French is rubbish! The cavern itself is dramatic.100 Germans at a time lived in there for years and it could shelter over 500 in attacks. From above ground there’s nothing to give the location away, but there were several man-made entrances. More tunnels were dug later to give access to the trench network above. The fresh white limestone was spread around the cave floor so the French wouldn’t see it, bringing the ceiling down and giving the place a slightly claustrophobic feel. Some entrances were walled off to try and prevent gas attacks.

At a steady 12 degrees all year round, it was both too cold for comfort and much warmer than the outside trenches which got down to minus twenty in winter. They had some water inside from wells or which dripped from the ceiling. Too precious to wash with, it was needed to cool machine guns. Lights were limited, so often the men inside lived in darkness. Areas were designated for command, sleeping, eating and for treating the wounded. As penicillin hadn’t yet been invented, and the cave was perpetually damp, no operations could take place down there. The soldiers were relatively safe from artillery, but had to endure the potential for being buried alive during bombardments.

The cave changed hands several times over the course of the war. Incredibly, the opposing sides actually shared the cave network for a period of months, the French in the south and Germans in the north chambers, separated by walls a few metres apart. The anxiety is unthinkable! At other times the audio guide made it clear the soldiers would have spent much of their time bored senseless, waiting for food, supplies, an attack, anything. One of the caves contains intricate metal objects and ornaments carefully fashioned from bullets and shell casings, one way to kill a few hours.

From the cavern we carried on east along the Chemin. The rain was steady and visibility poor so we carried on past a couple of places where you can see the old trench network and climb a tower for views over the battlefield. We’d a free aire earmarked in the small village of Corbeny, and we arrived happy to find two of the three places by the pétanque courts, overlooking the lake, were available. We’re set back from the road so are hoping for a quiet night before heading further south tomorrow.

Cheers, Jay

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!