Ghosts of Nerja: Echoes of the Spanish Civil War

The longer we spend in Nerja, the more we’re discovering of the small town’s past, specifically around the time of the Spanish Civil War. During the transition to democracy following Franco’s death in 1975, the country opted to avoiding dragging up/facing up to what happened during and after the war (for fear of the whole hellish thing kicking off again). Although this approach is gradually shifting, this era of history isn’t much advertised here on the ground, so we’ve come across most of these few bits and pieces below through word-of-mouth, or just spotting a sign here or there. Spanish history and politics is well beyond my meager means of comprehension by the way; this isn’t meant to be a historically accurate piece, just me relaying my own small experience of these events. I’ve listed them in the order I believe they took place.

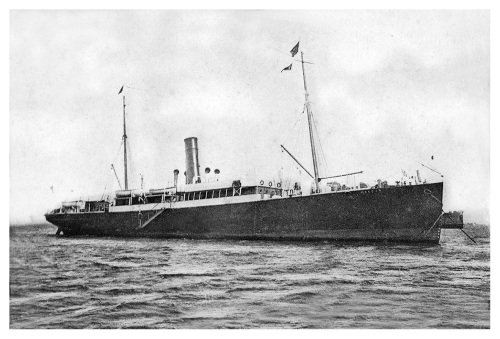

The Dolphin

Two miles west of our campsite, below an old coastal watch tower, lie the sunken remains of The Dolphin (also known as El Barco del Arroz, the rice boat). The beach alongside is named Calaceite, after the oil (aceite in Spanish) which lay thick on it after the ship was sunk 83 years ago, in January 1937, six months into the country’s civil war. In a lay-by on the N-340 a new sign’s been put up showing the location of the wreck, only 100m or so off-shore at a depth of around 6 to 8m, with a little history and photographs of the sea-life which has taken advantage of the wreck (the remains are located around this spot: N36.737589, W3.923715). Being so close to the shore, I couldn’t resist cramming my wetsuit into a rucksack one sunny, calm February day and cycling over there for a snorkel, with Ju acting as look-out and support crew from the shore.

I’ve been lucky enough to do a fair bit of snorkeling over time, plus a PADI scuba course on honeymoon with Ju over a decade back, but I’ve never visited a wreck before. I read up a little before heading over, which gave the experience more meaning to me, and when I first spotted one edge of the ship on the sandy bottom emotions ran through me, imagining the violent events which placed the 80m steamer onto the sea-bed to rest forever. I was thankful that, as far as I could tell, none of the crew were killed when she went down, so it was only the grave of a ship I was flying above, not that of men and women.

The story is summed up well on trasmeships.es, but goes like this: the Dolphin was in use by the Republican side of the war, those fighting Franco’s Nationalist forces. At the time, the Nationalists were attacking Malaga to the south, and the Dolphin was sent from Almeria loaded with rice, flour, cod and oil to help feed the forces and the city’s civilian population, which was inflated by thousands of refugees. Clearly the ship never made it, being destroyed on the way south by Franco’s pro-fascist allies of the time: Italy and Germany. First the ship was spotted by a German plane flying from Melilla in Morocco. Three more German planes were called into action which attempted and failed to torpedo the ship, causing the captain to ground it and for the crew to flee to the land alongside. After this the crew returned to the ship and, after being unable to unbeach it, a second German bombing raid took place. They missed, but this time the crew, who’d again gotten clear to land, wisely refused to re-embark.

With no air or sea support available, the Dolphin remained beached that night, although still in one piece until a roving Italian submarine spotted the sitting duck and sunk it with a torpedo. A couple of days later a final German air raid took place and this time managed to drop a 250Kg bomb into the centre of the ship, finishing it off and leaving it lying on its side alongside the beach where it remains to this day.

The sense of snorkeling over the wreck was a strong one for me. Wearing a 5mm hooded wetsuit and gloves I was warm enough even on a February morning for a 30 minute swim, although without weights I struggled to stay below the surface for long for close-up looks at the wreckage and wildlife. Even after eight decades below the surface of the Med, poles stand upright from the sea bed, and the sides of the ship clearly rise from the sand. Railings and other structures are easy to make out, although I’d no idea which parts were which, or even which end of the wreck was the bow. There were a few shoals of small fish around me, and the entire surface of the deck was covered in anemones wafting back and forth in the light current. The sign alongside the N-340 (and diving websites) talks of conger eels and octopus among other species, but they were perhaps better spotted with Scuba gear, I certainly didn’t see any. After swimming the length of the ship three times the cold started to seep in and I finned back to shore, thoughtful about the events which caused European nations last century to pour their efforts into such destruction.

The N-340 Malaga Road Massacre

Only a few weeks ago we were stood in front of Picasso’s famous painting of the infamous bombing of Guernica in April 1937. That painting was intended to highlight to an outside world the atrocities being committed in Spain, specifically by Franco’s Nationalist forces (although it’s clear both sides showed little restraint in the murdering which went on, Franco’s allies provided more advanced war-making machinery and better trained men than the republicans had from theirs). While the painting raised awareness of the fate of the small town in the north, an earlier and much larger massacre which took place on the N-340 between Malaga and Almaria, which runs about 200m from where I’m sat, received no such publicity.

The tragedy took place during the fall of Malaga to Franco’s forces in early February 1937, a few months before Guernica. Terrified civilians took to the N-340 to try and escape the incoming army along the only possible evacuation route, walking the unsealed road with whatever they could carry. Whenever I read of these kinds of events, the numbers involved are incredibly vague, probably entirely lost in time, hammered far too low or high by one side or another’s propaganda. In this case, sources state anywhere between 15,000 and 300,000 refugees took to the road. Around 4000 of those that stayed behind were systematically murdered, many of them raped first, so the desperate escape attempt is understandable.

What’s more difficult to understand is what happened next. The victorious Nationalist forces pursued the unarmed refugee columns and murdered swathes of them. One account has men being shot while women and children were allowed to continue, on the basis they’d be a burden on the Republican authorities. Other accounts don’t mention this, and have up to 5,000 men, women and children being strafed from air, land and sea as they tried to escape, specifically by Italian and German forces. Only for contrast, not to belittle the horror of the air-bombing in the north, somewhere between around 150 and 1700 people were killed at Guernica.

While Ju and I were wandering about one sunny morning around Nerja’s palm-lined meeting point, the Balcony of Europe, some kind of demonstration seemed to be taking place on the circular raised area facing the sea. A group of people dressed in walking gear were singing, standing behind a poster, maybe about 100 of them, with a few people stood in front listening and when the song had finished one of them spoke to the group in Spanish.

Our language skills weren’t up to deciphering events at the time, and we watched as they walked back up the road after a few minutes, thinking perhaps it was some argument against authority. It wasn’t, it was the Marcha Integral La Desbandá, an organised march which has taken place since 2017 following the route of the refugees, to raise awareness of the killing, to protest about the lack of support from Britain and France (they state the war wasn’t a civil war but a “nazifascist intervention against the Spanish Republic”) and to demand commissions are set up to investigate the genocide. In retrospect we saw relatively little local interest in the march, no TV crews, no crowds, no photographers other than the odd confused tourist (us). I’m not all that surprised, as we’ve seen time and again most of Spain just doesn’t seem to want to look back into this painful period of history. I’m not sure I blame them although if my family was murdered on the road, I imagine I’d see things very differently.

Graves, Graves everywhere

When Franco died in 1975, he expected his nominated successor Juan Carlos I (King of Spain) to continue as dictator in his place. Things didn’t turn out that way, and the king put steps in place to transition the country to democracy, giving up the majority of his power. Given the fact Franco had suppressed opposition for over three decades, there was a serious risk at this point that the two ‘sides’ of the war would re-emerge and blood would again be spilled. To avoid this, the country opted not to set up commissions to investigate the crimes of the war and during the dictatorship.

In the subsequent decades, it seems this fear has receded and pressure has built to look backwards to work out something like the historical truth, although not to identify the individual perpetrators of violence. In 2007, the Spain passed the Historical Memory Law, which recognised the victims of Franco’s force’s violence, and set about creating a map of graves for all those killed away from the front line (among other things). Before this map was created, the location of the graves existed only in the memories of friends and families of the victims, who had no choice during the Franco years but to remain silent, sometimes even having to live alongside their loved-ones’ killers.

I came across this map on previous visits to Spain, shocked by the fact I was likely driving past an endless series of unmarked graves as we wandered about the country. Many of the victim’s remains have long been removed and taken to the Valley of the Fallen (without the family’s consent or awareness). This is a highly controversial graveyard and (for many) an enormous monument to fascism near Madrid which, until recently, hosted Franco’s remains (his body was still there when we visited last year but has since been finally exhumed after a long fight). Other than the founder of his political party who remains buried there, not a single victim’s name is mentioned. There are no graves or gravestones, despite the fact over 30,000 people are interred there. I find myself looking at this map from time to time. Here in Nerja the nearest known grave (there are probably many more not included on the map) is about 3 miles away, alongside the Torrox River. I ran down the road across the river yesterday, glancing across at it, wondering what befell some poor souls up there.

The Lost Village of Acebuchal

As the civil war drew to an end in 1939, tens of thousands of refugees flooded across the border into France. We were once surprised to find photos of thousands of people at the (now abandoned) border post between the two countries at the eastern edge of the Pyrenees, ignorant of this exodus. Others stayed behind, through choice or not, and Franco went about consolidating his position by murdering or jailing tens of thousands more. Others opted for neither choice and turned to guerrilla warfare, continuing to harass Franco’s victorious forces right up until 1952. In Nerja, or at least a few miles inland, that’s what happened with a band of fighters hiding out in the mountains of La Axarquía (the local name for the region east of Malaga).

In an effort to remove support for the guerrillas, Franco’s forces cleared a small hamlet called Acebuchal in 1948, suspecting the inhabitants of helping the fighters. Around 200 people were forbidden from sleeping overnight in their homes which, given the remote nature of the village, effectively led to it being abandoned. The sources I read seem to suggest both Franco’s lot and the fighters harassed the villagers, a rock and a hard place for these poor folks. Eventually the entire village fell into ruin and stayed that way, defying one attempt to revive it until a tough-assed local couple managed to breathe life into a few buildings, paying for electricity to be installed, which attracted other renovators until the entire village has been rebuilt.

We were told about Acebuchal by others staying on the campsite alongside us when they knew I was into distance running and was looking for routes up into the hills to the north. The village is about 10 miles away from the campsite by road, uphill most of the way, although you can cut that in half by getting the bus up to Frigiliana. The last mile or so are on unsealed road, so if you opt to drive up be aware there’s a rough bit at the end, but the road looked in decent condition with no potholes.

The village was originally created as a stop-over for mule drivers taking fish, honey and the like north to Granada, and had a sudden remote feel to it for me, after the farmhouse-encrusted hills alongside the main road from Frigiliana. Running into the village, I found the restaurant (which has a great reputation) was open for business, but there were only a couple of other tourists knocking about on a mid-week February morning. Our campsite friends tell us the place is heaving with locals at the weekend, but I was in the middle of a 26 mile run and a full stomach wouldn’t have helped. One day we’ll hopefully get an easier chance to nip in for a meal: there are places to rent up there in the village if you fancy an over-nighter or three on the edge of the mountains.

I’ll leave you with a few more photos for Acebuchal, including some from the menu of the restaurant which has additional information about the village rebuilding process.

Thanks, Jay

Really interesting post Jay. It’s unbelievable, the atrocities that went on.

If you’re interested in finding out more about Spain, I can definitely recommend reading Giles Tremlett’s ‘Ghosts of Spain’, it’s a great read.

Cheers Mike – I’m currently working my way through Ghosts of Spain – hence the blatantly robbed title! Cheers, Jay

Great the you’re imparting this information – some of us Nerja residents are already fully immersed !

There is a Nerja History Group (http://www.nerjahistorygroup.com), established in 2002, to share information about Spanish History. We have meetings & guest Speakers who give a Talk each month about an aspect of Spanish history, followed by a day-trip the following week. Once per year, we have a multi-day trip somewhere within Spain. For the past few years, we have had our end of season lunch at Acebuchal. There is also very interesting book written by a local resident of Frigiliana, David Baird, called “Between Two Fires”.

Hi Christina, many thanks for the information, I’ll check it out. Jason

Another really interesting post. Thanks!

All very interesting

Thanks Jay – I really enjoyed that – I did the Camino walk last September and like you, picked up vibes about the unresolved issues of eh Civil war. Thinking of today, I cannot but think of similarities to Syria, although that is more religion as the cause, but you have outside powers – Russia (The Germany of the day) and Iran/Turkey (The Italians!) Hmmmmm

Hi, many thanks for this interesting piece. I’ve been visiting Nerja since 1982 and have noted how little coverage can be found about the Civil War there. I’ve read quite a lot of Tremlett’s and Preston’s writings on Spain but there seems little available specifically on Nerja. I had no idea about The Dolphin or the La Desbanda movement. I hope to get up to El Acebuchal one day. Thank you for sharing your experiences.

You’re very welcome – glad to be of some use – thanks, Jay