Electric (EV) Motorhomes of the Future

There’s no doubt the pressing need to reduce our impact on our environment will drive the uptake of electric motorhomes and campervans. Up until now I’ve assumed this is all a decade or two away for most of us. The UK government’s aiming to halt sales of new petrol and diesel vans by 2030, but that won’t mean we’re all scrapping our old vans and going electric any time soon.

Before writing this article I assumed it might be another 20 years before I’m driving a battery-powered motorhome, but I’m now thinking I was wrong. Even the most petrol-headed TV show, Top Gear, last night showcased electric vehicles towing ‘the future of caravans’ – so the future, it seems, is already here. That said, I’m still thinking it’s at least a decade away for us second-hand van buyers.

This blog post isn’t out to sell the idea of electric (or any other type of ‘clean energy’) camper. We don’t own an EV (car or van) and we’ve no plans to replace our 20-year-old diesel van with an EV camper. The nearest I’ve come to EVs is a couple of mates who own electric cars, and a few months working in the innovation department of an electricity company. I’ve a degree in physics, so have a basic understanding of the technology, but I’m definitely no expert on electric vehicles.

This post’s just food for thought folks. It’s a summary of what I’ve found rummaging around the internet. Maybe a starting point for a discussion about electric campers with a bit more meat than just ‘they don’t have enough range’ or ‘it’ll never happen’. We’ll have a look at the main alternative too – fuel cell hydrogen – although it looks to me like the electric vans will win out. OK, let’s go.

The Future is Already Here, Sort Of

A few bits of info have got me thinking change might happen a lot sooner. When we were recently updating The Motorhome Touring Handbook my ears pricked up when I realised fully electric campers are already among us. These are mostly smaller day vans, but larger panel vans and cab-only vans (base vehicles ready for conversion) have gone into (small scale) production too. You can even buy a fully-electric C Class motorhome being produced (again in small numbers) in Germany.

Just how practical are these vans? Range is an obvious concern, as is cost and access to a charging network. But it seems likely these will all quickly improve as uptake cranks up. Let’s have a look at these all below, but first, what’s driving all this innovation and change in the motorhome and campervan world?

The Big Drivers for Change

Internal combustion engines pollute the air and generate carbon emissions which contribute to climate change, we all know this. Older motorhomes in particular are villainous when it comes to coughing out black smoke. Ju and I should know, none of our vans have been less than 15 years old. Our current one gets about 23MPG. It’s as aerodynamic as a brick and it weighs a ton. Well, three and a half tons.

Governments have been slowly taking action for decades but the pace of change feels like it’s about to speed up. The EU has been tightening emissions standards for a couple of decades. The UK government charges higher rates of road tax for more polluting vehicles and offers grants to reduce the price of new electric vehicles. Most countries in Europe now have low emission zones, an increasingly-complex and widespread landscape of geographical areas restrict access to older vehicles. I imagine society will gradually change too, becoming less and less accepting of those of us driving ‘dirtier’ vehicles as the years pass. These are all external forces which will push many of us away from internal combustion engines.

And then there’s our own desire to change. My life’s so far been lived with a backdrop of themes – the cold war when I was a child, IRA bombings, the collapse of communism, international terrorism and wars, and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic. It seems likely climate change and its affects will form the final theme, the most enduring and perhaps the most personally influential on me.

I’ve already found myself thinking more about my impact on the world. It’s not all about guilt and accepting a lower quality of life. It’s a big positive thing for me. It’s helped me feel entirely comfortable living in small spaces, feeling less pressure to consume gadgets/books/cars etc and I now eat less meat that I ever have. This is all a win-win for me: I’ve been financially, physically and emotionally fitter as a result. Happy days!

The same could be true of electric motorhomes. It’s not too hard to imagine a world where real-world battery range has improved to 350 miles, fast-chargers are widespread, campsites and aires provide some fast and lots of slow-charge points so the battery recharges during our stay. Vans would no longer have Calor or LPG tanks, everything in the van would run from batteries with a powerful built-in inverter: an induction hob and oven/grill, water and air heaters, microwave, hair dryer, fridge, TV, everything.

With no engine, less servicing will be needed and the dreaded 2am wake-up call from someone starting their thundering diesel engine alongside us on an aire will be a thing of the past. With always-on internet connections and Tesla-like cameras plus software keeping an eye out, the risk of break-ins and thefts will drop. We’ll have free access to low emission zones and may well be charged less for toll roads, bridges and tunnels. Maybe a brave new motorhome world is on the horizon.

Cost & Range of Electric Vans Now Available

When I started researching this post I was surprised to find just how far the electric vehicle camper and motorhome market has already come. It’s now possible to buy fully-electric (BEVs – battery electric vehicles) vans and either self-convert them or get a professional conversion done. Here are a few examples along with the costs (new vans already have a government grant deducted from their prices below).

These are all BEVs – battery electric vehicles – so they only have batteries and no ‘hybrid’ combusion engine. Some are van-only (so you’ll need to pay for conversion to a camper/motorhome) and others are already converted as stated below:

- Second-hand 2014 Nissan E-NV200s can be had for around £12,000 plus VAT for a short wheel base, or £18,000 plus VAT for a long wheel base. These have a real-world range of around 70 to 80 miles. Glyn Hudson converted one of these to a compact camper for around £3k (doing the work himself) and blogged about a 2,500 mile trip to Southern Spain in 2019. It’s fascinating to watch his videos and real this blog about real-world experience of EV camper touring.

- Newer E-NV200s with a 140 mile range are currently for sale on Autotrader for £22,000 plus VAT.

- Sussex Campervans sell professional conversion E-NV200s, pictured above, starting at £60,000.

- The Iridium Electric Motorhome with a claimed 300 km range (250 miles) costs €160,000 (£136,000 – it’s not clear if VAT is extra). A 400km version is also available.

- Fiat have a range of e-Ducato vans, with a 230 mile (of city driving) version costing £65,000 plus VAT (plus conversion costs).

- Ford’s e-Transit comes in at £43,000 plus VAT with a 196 mile range (plus conversion costs).

- VW’s e-Transporter costs £42,000 plus VAT with a claimed range of 82 miles (plus conversion costs).

Alongside EV base vehicles from the other main manufacturers (generally with lower ranges than those above), Knaus have also produced a hybrid C Class concept camper. This has a combusion engine to extend the rather limited 56 mile range. This isn’t for sale, so no price information’s available.

Other than the self-converted second-hand small e-campers, prices look very high at the moment. EV running costs should be lower but not necessarily (especially if you can’t charge at home). But all this will change with time. The cost of making increasingly-cleaner diesel and petrol engines will go up. Governments will ramp up taxes on fossil fuels. Production costs for EVs will fall. At some point EV campers will become cost-comparible with their combustion engine equivalents. When? Hopefully by 2030, or there’s going to be a shock to the motorhome and campervan industry!

Payload and Licensing

Like combusion engine vans, EV campers have a Maximum Authorised Mass, the most they can legally weigh while out on the road. Anyone in the UK with a full car license (category B) can drive a motorhome up to and including 3,500Kg MAM. If you want to go above that, you’ll need a C1 license. I’ve got this category, as I passed my tested before 1 Jan 1997. If you don’t have C1, you’ll need to take lessons and pass a test in a 7.5 tonne lorry, probably costing you around £500. The government allows cat B license holders to drive electric vans up to 4.2 tonnes, but only for carrying goods, so no use for EV camper owners.

The question is: can EV base vehicles be converted to motorhomes, adding a load of weight, and still have a reasonable payload for people/pets/clothes/water/food/crockery etc? I don’t know the answer, but as a very rough and ready analysis, these guys converted a combusion engine Sprinter, which added about 1,000Kg to the van weight. The e-Ducato specifications are here, and show that the 3,500Kg MAM version weighs 2,340Kg unconverted (the kerb weight). Adding a 1,000Kg conversion would bring the weight up to 3,340Kg, so practically no weight left for all your stuff – no good! Depending on whether the e-Ducato chassis can take it, the converter could ‘uprate it’ to maybe 4 tonnes, but that would impact who could legally drive it, and the battery range.

That’s only a very simple comparison of course, and EVs wouldn’t need separate leisure batteries, diesel/petrol or LPG tanks, which would free up more weight. It does look like it’ll be a close-run thing in terms of payload though.

EV Recharging Options

Instead of litres of fuel, EV ‘tank’ (battery) capacity is measured in kilo-Watts (kWh). Recharge speeds are measured in kWh (kilo-Watt-hours). To get a rough estimate of how long it would take to fully recharge your batteries, you divide your battery capacity by the recharge speed. A few examples are given below for the79 kWh battery version of the e-Ducato (147-175 mile range):

| Connector Recharge Speed | Time to Fully Recharge a 79kW e-Ducato (Rough Estimate) |

| 3kW (3 pin plug at home or campsite) | 26 Hours |

| 7kW (fast home charger) | 11 Hours |

| 11kW (standard on the 79kW e-Ducato) | 7 Hours |

| 50kW (optional) | 1.6 Hours |

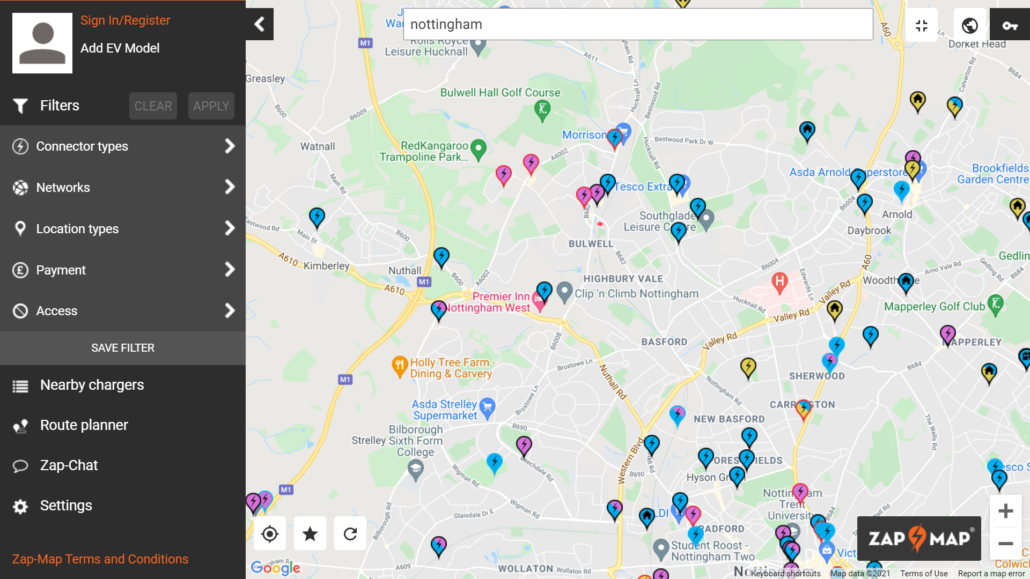

With the optional 50kW e-Ducato charger we could add 60 miles of driving range with a 30 minute charge. To get that speed we’ll need to use one of the public chargers though, we won’t get more than 7kW at home. Instead we’d need to use one of the public network of chargers, which appears to mean:

- (a) finding one which has the right kind of cable connector for your van,

- (b) paying much more for the electricity than your home tariff,

- (c) using one of a plethora of apps and cards to buy the recharge,

- (d) hoping the charge point isn’t in use or out of service when you need it,

- and (e) trying to fit your van into a car-sized parking space (and hope there’s no height barrier to access it).

On the plus side there is an increasingly-large range of EV charge points available in the UK, as mapped out on the zap-map.com website (pictured below) and app. This doesn’t show campsites, which might allow us to recharge our vans on their electrical hook-up points for an additional charge. However, EV’s are power-hungry beasts and (I’m only guessing here) I doubt many campsites have electrical supplies which can cope with lots of EVs charging simultaneously. There’s an obvious opportunity for campsites to upgrade their electrical systems for EVs, but that’ll take investment and time.

For the time being, trying to tour the UK in anything bigger than a small van looks challenging to me (although I’ve never tried it). Chargemap.com maps out EV charge points across Europe, so you can get an idea of how big the networks are in each country.

What About Hydrogen?

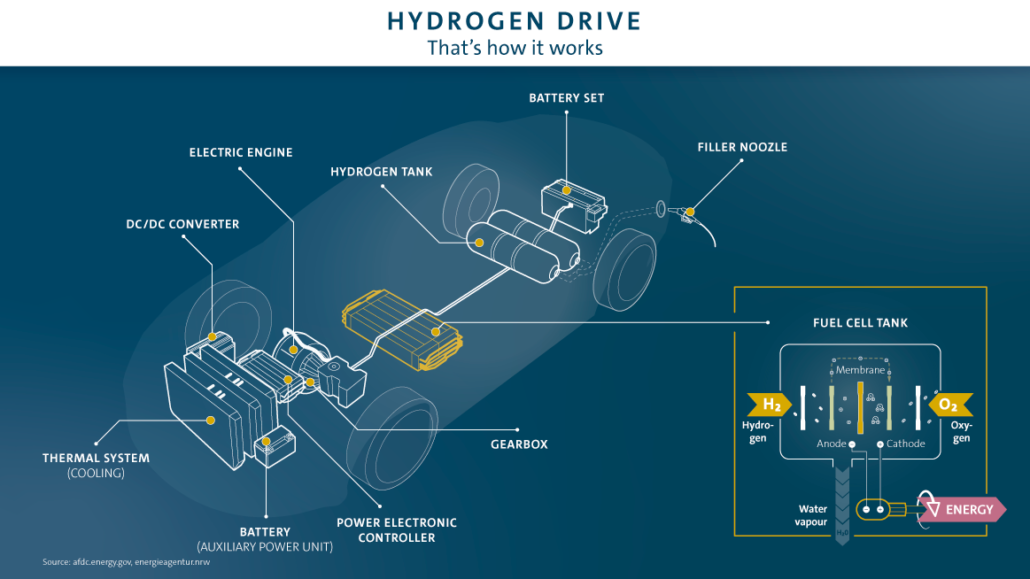

So far I’ve concentrated on plug-in EVs. These use batteries to run electric motors which drive the wheels. But a competing technology might end up dominating the van and lorry markets: the hydrogen fuel cell. These have the advantage of fast recharges and long ranges, much like existing fossil-fuel engines. You connect them with a pipe to a hydrogen pump which fills tanks in your van in a few minutes. Within the van a fuel cell converts the hydrogen to electric power which runs the motors and drives the van. The only waste product is water. A small battery is used to smooth out demand and provide a short-range back-up if the hydrogen runs out.

From the sounds of things, hydrogen is an obvious winner. Faster to refill, longer range, not as heavy, happy days? Apparently not. VW explained in this analysis they’re focussing on plug-in EVs rather than hydrogen in the next few years. They don’t see hydrogen as a viable technology for cars (they don’t mention vans or trucks) due to the relaively low efficiency of producing the clean energy needed to obtain the hydrogen, compressing it, transporting it, running it through the fuel cell and then the electric motor. Plug-in EVs have the jump on Hydrogen too. As of November 2021 there are around 17,000 locations with public charge points, catering for up to 46,000 EVs (not including all the charging options for cars on house drives). There are only 11 hydrogen refill stations across the whole of the UK.

In Summary

The days of petrol and diesel vans are coming to a close, but not for a while yet. New fossil fuel vehicles will be sold in the UK until at least 2030, and perhaps much longer if public EV take-up isn’t enough, or the infrastructure to recharge isn’t in place. Motorhomes look like a serious challenge to EV battery technology due to their weight and lack of aerodynamics. But technology is progressing quickly and costs will come down. I still think it’ll be at least another decade, more likely two decades before we’re the proud owners of a used EV motorhome.

What are your thoughts on electric motorhomes and campervans? Can you see yourself driving one in the next few years? Let us know in the comments below. Cheers, Jay

Thanks Jason,

Sadly, I think Hydrogen is facing it’s Betamax moment: EVs are going to be the accepted solution before hydrogen gets its infrastructure shizzle together. Discretionary infrastructure building doesn’t seem to happen in this era.

What I’d love to see is some kind of end to end environmental impact of EVs, Hydrogen and ICE vehicles. As an ignorant but interested bystander I’m concerned that the extraction of materials to build EVs can be a nasty business and is there a plan for decommissioning? Year 2 of a smartphone battery life is never as good as year 1 and after much longer than that you’re into battery palliative care.

Also, I’m not seeing much discussion about the long term availability of the ingredients required to put EV powertrains together.

You need to get the Pop Master into your caption writing BTW. Zagan squashes beetles in Norwegian Wood seems like a missed opportunity.

I can’t quite work out the Hydrogen thing – it looks so much more convenient for larger vehicles but then some manufacturers are saying it’s so much less efficient end-to-end even for HGVs. I’d need to do a fair bit more research to grasp it better I think.

It hurts my head trying to work out what’s ‘green’ and what isn’t. And just how ‘green’ do I want to be? Taken to extremes none of us would be having kids (another generation of lifetime carbon use), driving anywhere, eating any meat or dairy, buying anything new, flying anywhere etc. At a less extreme level, as you’ve said, trying to understand whether it would be better for the environment to sell our diesel van and buy and EV one is hard too. There’s carbon sunk into the manufacture of both vehicles – how long would it take to get that back on a new EV-powered van?

It’s going to be an interesting time I think and I imagine EV motorhome uptake will be very slow. I’m 49, maybe another 40 years on the planet with luck. I wonder just what the world will look like when I shuffle off and leave it to the next generation.

Cheers, Jay

Hi Jason,

A thought provoking blog and something I have been pondering as well. The Government’s 2030 zero emission plan will no doubt be challenging for the motorhome and campervan converters, particularly attempting to balance the weight and range factors. Obviously, we won’t need to scrap our existing diesel vans for some time but it will be interesting to see how social pressures could/may change over time regarding the use of polluting vehicles.

On a related subject, I considered whether we should change our four year old car for a new electric one. It transpired that there is far less environmental impact to continue to run a petrol car than produce a new EV. The author of an article I read looked at whole world emissions as a result of building and running a new EV versus the emissions from using an existing car. The existing car won hands down. Therefore I don’t think we will be changing our car until much closer to the end of its life. Therefore, I think the same argument can be applied to our campervans and motorhomes.

It will be interesting to see how this all pans out over the next few years. There does appear to be a greater enthusiasm for EVs and it would be great to see a far better and integrated charging network in place. As vehicle manufacturers invest more and more in alternative technologies and demand (and therefore sales) hopefully drive prices down, then inevitably there will be a gradual change that will benefit the global climate.

Thanks Peter

“Therefore I don’t think we will be changing our car until much closer to the end of its life. Therefore, I think the same argument can be applied to our campervans and motorhomes.”

This makes sense to me too. I’m no ‘green warrior’ I admit, but I do find myself continually challenged by the ‘what’s greener, this is that’ question. In terms of driving, I tried comparing our aged 23MPG diesel van with a driver and one passenger, with two people flying between the same destinations on a long trip (East Mids airport to Malaga) and the van won hands down (using https://www.carbonfootprint.com/ or similar). Seems bizarre to me?

Cheers, Jay

It’s never particularly intuitive is it?

I just tried to do some basic maths on the problem, just for the fuel consumption. It seems that the fuel efficiency for a plane these days is between 3 and 4 litres of fuel per passenger per 100 km. A flight from East Midlands to Malaga is in the ballpark of 1800 km, so at 3.5 litres per passenger, that would be 63 litres of fuel per passenger by plane. Add a second person and it is 126 litres of fuel.

If you put 126 litres of fuel (28 gallons) into your 23 MPG van, then your range is about 644 miles. Nottingham to Malaga, by road is about 1,500 miles – so your fuel isn’t even getting you half way!

I hope my maths is halfway correct!!! (Of course, I know that fuel isn’t the only factor in the calculation – but it will be the most significant)

I’m permanently confused by all this stuff! Your maths looks good to me, although I guess if we ran out van on aviation fuel we might get a bit further? Cheers, Jay

You might be surprised – as far as I understand it, Aviation fuel is basically just ultra filtered diesel, to a slightly tighter spec – it’s not necessarily better, just more reliable (you don’t want something to be wrong with the fuel in your plane!)

Just pulled up this BBC carbon emissions article comparing flying with other forms of transport. It has ‘secondary effects from high altitude’ roughly doubling the impact of flight compared with (presumably) fuel alone. Maybe just the fact we’re driving at ground level makes all the different?

https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-49349566

Cheers, Jay

Hi Jason. Long time …etc.

Elon Musk will push the boundaries of battery tech.

10 years ago the Nissan Leaf did about 80 miles.

The range of high-end EVs now approaches or exceeds 400 miles (Merc/Tesla).

500% in 10 years.

A motorhome is more suited to waiting at a charge point for a while than a car on a long journey.

A motorhome chassis can theoretically carry a whole heap of batteries and maybe a kilowatt or more of solar panels. Endless torque and easier to implement 4×4.

Imagine 100Kw/hrs on board. That’s an off-grid dream. Maybe a wind-out 1kw solar awning???

It may need new regulations, to allow an extra tonne of weight on a regular license.

Mind you, how much does my 3litre diesel engine, gearbox, clutch assembly, plus fuel, oil and coolant weigh??

We just installed 9kw of solar panels on the house, with 3kw to come.

Next step is an EV car charged at home from solar, and some battery storage. I want to get out of fossil fuel dependency ASAP and our experience with solar panels/batteries while living off-grid in Humberto was a revelation.

If your ever in SW France … come say Hi to Humberto (sleeping in our barn at the moment).

Hi Lee

Greetings from sunny Kimberley! OK, it’s not sunny, but our panels are still part-powering & subsidising the electric radiator we have running – pretty cool! Yep, the new tech will get better/lighter/cheaper/more attractive as time goes on. But then stuff doesn’t move as quickly as anyone would like IMHO. Smart Meters make a lot of sense, for example, and the UK *should* have completed the rollout in 2020, but are still only haf way through.

When I worked in E.ON’s new technology business over a decade ago they were expecting/hoping for the EV revolution. As of 2020 only 0.6% of the UK’s cars are battery electric. That’s up from 0.1% in 2015, but a long old way from the revolution. Don’t get me wrong, I’ll love it when it all happens.

Cheers, I hope that barn’s warm and thank you, we’ll give you a shout if we’re down that way next year. Jay

Hi – Thanks for thought provoking post. We are about to start our motorhome adventure and are hoping to buy in France as my sister lives near Toulouse and will be registering it there. Are the EU/French regulations for owning/driving >3500 the same as UK ie 1997 =C1 or have they changed recently? I wish that I could buy a greener vehicle now but simply cannot wait and mentally offsetting running a house with motorhome living… we will have as much solar/other charging as possible, of course!

Hi Kim – sounds like a great adventure heading your way! Sorry, we’ve no idea about the law when it comes to driving a French-registered van. I’d guess it’s the same as a UK van but only a guess.

Beat of luck & happy travels, Jay

Blog and general comments all very thought provoking, and as Peter indicated it’s not as simple as it seems when it comes to batteries – they contain some pretty horrible stuff and a lot of it is dug out of the ground by people in very poor countries.

I have had my van from new (converted Ducato) for 4 years and health allowing I am looking forward to another 10 before selling it, BUT – will anyone buy a used diesel van in 10 years time? And when the pandemic is over (ever the optimist) I expect there will be thousands of used vans going begging in the UK when the Costa-del-Sol crowd can go back to doing that.

Well, I guess there’s nothing to do but wait and see. Interesting times!

Regards, Joe.

Hi, well at 75 I suppose a decade will do us and 2 decades!! If I could get a pure EV for the price of a new Fiesta, I would be at the dealers 8 o’clock in the morning. How are we meant to be able to afford them, given the huge amount of old cars on the road today?

Good question. I guess they’ll get cheaper and the old cars/vans will eventually get scrapped. How quickly will that happen? No idea. Cheers, Jay

Hi Jason

Great thought provoking blog thank you.

Also good to hear from Lee & Humberto on the comments.

My own thoughts are that battery technology needs to improve first and that given the cost of ev vehicles the uptake will as you’ve mentioned be slower than some anticipate.

Looking forward to reading about your next adventures on the road.

I’ve had SolarPV panels and EV’s now for over 10 years but never a motor home. It seems to me in principle that an EV motorhome should be feasible given that a high percentage of the time you use a motorhome is in a static plugged in position. With solar panels or awning you might be able to generate say 2-3 kWh/day so maybe only 50 miles of motoring if you are parked for a week but topped up by say 2kwh/hr if plugged in at campsite.

This is a cool perspective! It’s interesting to see someone who isn’t an EV expert excited about the future of electric campervans. Maybe electric campervans won’t be as far off as we think.