Oświęcim, Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland

Dave the motorhome’s tucked in for the night in the official car park at the Auschwitz Museum, at Oświęcim in Poland (N50.02886 E19.20039). There are a whole raft of other parking places on the road here, each with an accompanying high-vis-official waving you in with gusto – this is the parking for you! We chose this one as we knew we could stay here overnight. It’s rammed busy, with perhaps 30 coaches in here at the moment, but we guess it’ll quieten down later. It’s £5 per 24 hour stay.

Dave’s crammed in at the moment! Our parking spot in Auschwitz, one we’re able to leave whenever we like…

What seems like a long time ago we found ourselves in a heaving full car park, the Volksfest and accompany dirndl-wearing locals had crammed full the small town of Dachau, Germany. A wee bit pushed for time we legged it around the museum at the infamous concentration camp, which was flooded with sunlight and families. Sickening stories were told in photos of mistreatment of innocent people, and of terrible experiments on prisoners justified by the possibility of helping save German soldiers and airmen. The camp was clean, open, airy and of course disgusting, but left both of us a little cold (Ju’s wrote about it here). Another, much smaller and less infamous camp in Trieste affected us both more deeply (I wrote about it here).

When we left Dachau our common view was we’d seen enough. We felt that there was no more we could see, after all, we couldn’t understand why the Nazis, and the many other people they enabled, could sink themselves to the level of the sub-human, while somehow being utterly convinced those they tortured, terrorised and murdered were in fact the sub-humans, worthy of nothing but contempt and ultimately death. And yet today I find myself writing this from just outside the gates of Auschwitz 1, part of a huge complex which makes up the World-infamous Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. Why are we here then? It’s a good question.

I would like to say we’re here on a pilgrimage, but the simple fact is the place was on our route. We could still have bypassed it of course. Within the centre of Krakow a whole forest of of signs advertise trips here, it’s only an hour’s run from the city. Auschwitz would obviously be heaving with folks on tours, or who’d flown into the city on a cheap flight, and for many of them coming here would be a tick in the box, arguably the most evil place on the surface of the planet: done. The thought of arriving in such a black place to find myself in among a throng of yabbering idiots, if you’ll excuse the clear snobbery in the statement, wasn’t tempting. There’s also another good reason for me not to visit these places: I don’t cope very well with them. The Ground Zero museum in New York, Risiera Di San Sabba in Trieste and even the small monument to deported Jews we found in Northern Italy at Borgo San Dalmazzo all had me sobbing as though in personal loss. I’m a (somewhat over-) grown man, I don’t find this embarrassing, but I find it painful. The thought of the pain, fear, suffering and loss, and the pointless injustice, cuts me.

So why are we here again? I guess we came for the reason most people do: because to not come would be a cowardice.

The road here was narrow, but with a perfect surface which made lorry dodging easy enough. From 45 minutes away the signs made sure we couldn’t miss the place: Oświęcim, sometimes on huge green arrows half the size of Dave. The Germans couldn’t pronounce these Polish names either, and had long called the place Auschwitz, but the Poles clearly prefer their name these days (and why shouldn’t they), the name ‘Auschwitz’ only starts to pop up on little brown signs as you’re nearing the town. The area’s green with leafy trees and fields. Houses and villas are spread out around the road, and a train-line ran parallel for a while, giving us a bit of light relief as Speed-Meister-Dave overtook some rolling stock. It’s a pleasant part of the world: far from everything.

Eventually the road turns right and the array of green fluorescent jackets and rotating arms told us we’d arrived. Again more relief as the arms often tried to wave us into car parks on opposite sides of the road, each arm-owner attempting to out-do the other in whirling action. I hope they’re on commission.

We pulled in and Ju took a phone call. It’s insurance renewal time and she’d a few folks to talk to in the UK about our peculiar situation. So far we’ve had a few folks refusing to offer us insurance as we’re (a) not currently in the UK (b) don’t plan to move back into our house which is being rented out or (c) the wind’s blowing south easterly today. The best quote to date is £1200, which seems like rather a pleasant fate when parked up where we are, but will hammer our funds nevertheless. After relaying a phone book’s worth of info the fifth time, we had a promise of a text back with a quote (hopefully an SMS message will have enough characters for the huge sum requested) and we set off for the camp.

We entered via an Alton Towers queue, even bumping into Louise and Colin again, as we’re all clearly following the same set of places to visit around here. The place draws as many as we expected it to, which is of course a good thing for humanity, if not for you as an individual as you wonder if this is indeed the queue for tickets – the signage leaves a bit to be desired. I withdrew into myself. I knew what was in here, I’ve seen it many times on the TV and read about it time and again over the years. I had an inkling of the level of depravity the SS and their cohorts had sunk to, and the mirrored terror and hopelessness of those they abused beyond belief. I’d even tried to read up to understand why it all happened; why Jews in particular were deemed unfit for existence, why Germany chose to employ its ingenuity and power for such a disgusting act, why no single organisation (including the Christian Churches) stood shoulder to shoulder with the Jewish people. No answers were forthcoming, just arrogance and stupidity. I even read of one immensely brave/suicidal chap who’d deliberately got himself interned here, incredibly escaped against massive odds, and wrote a detailed report on the full-swing holocaust in action, only for it be shelved in the UK and the US, ignored, no outcry, no broadcasting of the news so those surviving Jews might be alerted to their fate and fight.

Our tour guide, Anna, spoke to us through radio headsets. Her voice seemed about to break up at any time; she looked far too tough for this to be the case but all the same her dialogue and tone added a deep level of sincerity and importance to what she was showing us. She elevated the whole experience. Like sardines we crammed our way through some of the tighter areas of the place, all of this lost on me as I drifted into a pretty grim corner of my world, my composure collapsing completely at the sight of an enormous mass of woman’s hair, cut from the dead for re-use as stuffing or for fabric. Fortunately the rest of the place didn’t have the same debilitating affect on me, the exhibits became much less personal as we took the bus to Birkenau.

Birkenau is the second of three areas within the complex (the third’s been completely destroyed) and was the place where the real business of genocide was played out. It was here where Jewish folks came in all innocence to find themselves gasping for breath beside their friends and neighbours as the poison was dropped into the gas chamber described to them as showers. It was here that tens of thousands of people came to be worked to death by the Nazi war machine, living in conditions where killing another for a piece of bread was the norm, and those who emptied the latrines of human waste were thought to have a good job, since it was done under a roof. The whole thing is unimaginable, fortunately for us, us lucky folks who’ve only lived through peace and democracy. Anna pointed out the fact the Germans could always kill more than they could burn, the crematoriums ran at full pelt, the ashes strewn everywhere around us, including under our feet.

At the end of the tour Anna made a short speech, reminding us what Auschwitz stands for, as a memorial, as a reminder. Those who perpetrated these acts, she told us, planned well. The task they gave themselves was enormous, only the most intelligent could achieve what they did. Administrators, engineers, logistics experts, all worked within a huge state-managed machine to murder on a scale which cannot truly be believed. Most of them escaped justice. As an example, as of today, Alois Brunner is the number 1 Nazi being sought by the Simon Wiesenthal Centre. He’s thought to be responsible for the lives of tens of thousands of Jews shipped to death camps under his supervision, and if alive is 101 years old. Back in 1987, he said this to a US newspaper:

“All of [the Jews] deserved to die because they were the Devil’s agents and human garbage. I have no regrets and would do it again.” —Alois Brunner, interview in Chicago Sun-Times, November 1, 1987

His views of the world are not unique. There are many who see themselves as superior to others based purely on their religion, the country they happened to be born in, or their race. It’s rather unlikely any of these people will come to Auschwitz, and if they did I doubt it would bring them to a more enlightened position. However, for the rest of us, the lessons of Auschwitz are clear: we must never enable the conditions to re-occur where sadists, bigots and racists are given the power they desire. Hitler started small, gradually building support for his ideas, and using hatred for his own purpose; others will try to do the same, especially when entire peoples are weakened by economic distress, like now. From the way Anna spoke her last few words to us, it sounded to me as though she almost expected another Auschwitz-scale atrocity, telling us the evil with humankind remains.

Auschwitz was an experience I will be unable to forget, I’m glad we came here and that chance placed it on our route. I’m glad that we had such a wonderful guide. I’m also glad the sun’s shining, a bird’s tweeting next to us as the diesel engines of the coaches fire up and rumble off up the road, and that there’s a cold beer in the fridge.

Jason

P.S. Wielding a camera today was beyond me. Ju took these photos, and said the act of using the camera helped insulate her a little against what was being shown to us. In some places in the camp photographs are not allowed and of course we respected this request.

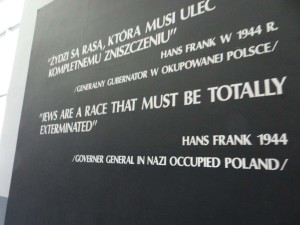

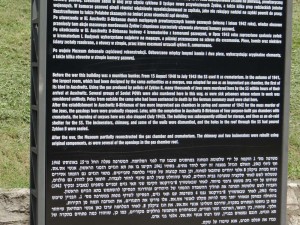

- The Nazis were normally extra-ordinarily careful to hide all evidence of the holocaust in the speeches and documents. They failed sometimes though.

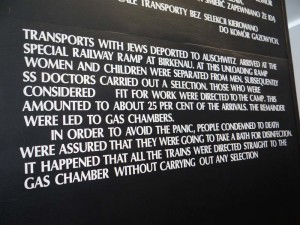

- Photos of folks arriving show zero clue of any panic, they were completely un-prepared. Almost all Jews were killed within 2 hours of arrival, others lasted typically a couple of months.

- Photos like this should not exist, they were expressly forbidden. Some do though, this one clearly showing men being selected for work (flick of the finger left by the SS doctor) or immediate death (flick of the finger right).

- The SS were skilled at managing the flow of people into the death chambers.

- Folks arrived here in cattle trains, expecting this to be a stop-off on the way East to somewhere they’d be resettled. The Jewish race has long been subject to such enforced movements, and had no clue this time things would be different.

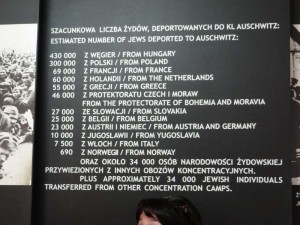

- Numbers beyond comprehension.

- Shoe polish brought by those who were killed. They expected a decent life, but were given either immediate death or months/years of filth, agony and disease.

- There aren’t that many people left who can read the script at the bottom.

- Shoes, Christ, a lot of them and this is nothing.

- Auschwitz, tiny compared with Birkenau

- People were told to bring just their most important things. Folks wrote their names on their cases, expecting to be needing them. They were stolen by the SS, their contents to be sold for the war effort (some SS officers helped themselves of course).

- Very few escaped the camp. Those that did had to get past the SS who had ousted all the Poles from the surrounding area and taken their houses.

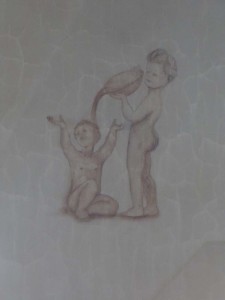

- The German Red Cross would make camp inspections from time to time. The visits were obviously very well handled, and allowing inmates to draw on the walls helped create the illusion of comfort.

- Those unable to work, including Jewish Germans who lost limbs in WW1, had no chance. On arrival they were sent straight to the gas chamber.

- Canisters of the gas used to kill. Initially the gas was developed to kill insects, later to kill people, “as though they were insects” said Anna.

- Haunting photos of people killed in the camp. Most of them stare ahead, hopeless. One had a tiny smirk. Another looked manic. I checked the dates on the last one, he was dead within 2 weeks.

- Incinerators.

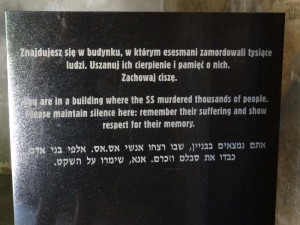

- Respect indeed.

- ‘Work Makes Free’ Irony, since you were expected to be worked to death. Someone stole the sign and cut it up, for a reason not explained to us. It has since been recovered, but this one’s a copy.

- Latrines in Birkenau. There was no running water. In fact there was no water anywhere, but for a half litre in the morning. Folks took to supping water from puddles, which killed a fair few of them.

- Former horse stables ‘converted’ for humans. These places were rammed full of people kept in conditions unfit for any animal.

- A memorial to the dead, and a reminder for the future.

- Arrival at Birkenau

- Birkenau, where the trains were unloaded before reversing back out into the World to receive another load of innocents.

- Birkenau

- Birkenau. You can only get a full sense of the scale of the place from the lookout tower at the entrance. It’s huge.

- The attempt to destroy the gas chambers was only partially successful. All around this area the ground’s suffused with human ash.

- Only the weak slept on the concrete floor, those stronger would fight their way up from the filth and cold. Anna said that we should not judge them, and surely we’re in no position to do so.

- Birkenau. This place has been a museum for 60 years so remains well preserved.

- Birkenau

- Birkenau

I couldn’t visit. But thank you for trying to put into words what you found there.

Thanks for sharing Jay – very moving. Don’t know whether you’ve come across it already but there is a great book by a Jewish POW who was in Auschwitz for a while – Victor Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning. The book was originally named “Nevertheless, Say “Yes” to Life: A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp) chronicles his experiences as a concentration camp inmate which led him to discover the importance of finding meaning in all forms of existence, even the most sordid ones, and thus, a reason to continue living.” (last bit taken from Wikipedia).